It seems obvious that cleantech requires innovation — in technologies, products and business models. However, is innovation (making new things) as important as quality (taking existing things and making them better, simpler, easier to use and cheaper)?

There are three reasons why quality really matters in cleantech.

1. Failures can set the market back

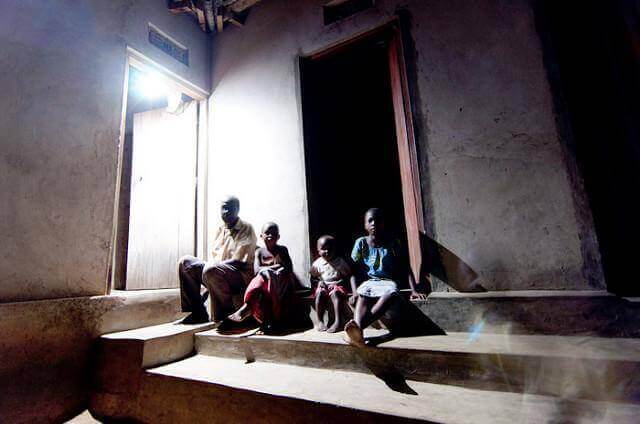

It’s clear that clean energy technology could bring power, water and modern agricultural capabilities to millions of poor rural people in Africa and Asia. Keeping costs lower is important, but not at the expense of reliability.

I learned this in early 2015, when I was doing a project in a South East Asian country where about 14 percent of the rural population had access to electricity at that time. A World Bank-supported project sought to deploy 12,000 solar systems in homes, each coming with a subsidy of $100. But the initiative failed because the batteries would not last. Subsequent donor-supported programs to promote rural solar electrification would have to spend money to address the negative perception people had about solar home systems.

It is only by close collaboration between suppliers and buyers that quality is attained.

A later effort by the World Bank led to the installation of more than 5 million solar-home systems by IDCOL, a Bangladesh non-banking financial institution — even though the upfront costs were steeper.

M. Rezwan Khan, a Bangladeshi academic in charge of the quality aspects of the rollout, realized early on that solar home systems equipped with batteries that were used in cars (this was in 2002) failed in less than two years. He decided to switch the car batteries with industrial-grade batteries, which had a warranty of five years.

The industrial-grade batteries were designed to withstand conditions of being discharged almost completely and then charged back again. This was how people used their solar home systems. The problem was that these batteries were about 50 percent more expensive than car batteries.

Initially, the World Bank had apprehensions that these would make the systems prohibitive for the rural Bangladeshi poor. But Rezwan Khan and the IDCOL management insisted the costs of product failure would be a much higher one.

2. Ensuring reliability is imperative for adoption

The energy-efficient LED lighting market in India has been growing rapidly. LEDs are light-emitting diodes, sophisticated semiconductor devices. They require specialized electronic components called LED drivers to convert the higher-voltage, alternating grid current to low-voltage, direct current and keep it at a specified level.

In the early 2010s when LEDs came into the market, LED lights had a high rate of failure in India. The transformers used in India’s distribution infrastructure were old. Lines were strung overhead. A crow swinging on one could make an energized line touch an “earthed” one. This meant the power quality in the distribution infrastructure often fluctuated wildly. This fluctuation led to the failure of LED drivers, which in turn led to the failure of LED lights.

Promptec Renewables, then a startup venturing into the LED market, started seeing very large failure of lights, especially street lights. It came up with a surge protection device, which absorbed these fluctuations and protected the LED drivers. The founder of Promptec Renewables, Kiran Moras, later sold his company to Havells, a large Indian electrical goods company.

3. A focus on quality will help mitigate risks

Take the case of PR Ecoenergy, an Indian company that manufactures biomass briquettes, compacted blocks of dry organic waste that can be burnt to replace fossil fuels. Its customers, large industrial companies, were hesitant to make the switch because they were not sure whether the new technology would work as expected or if there would be an assured supply of biomass briquettes.

To win over customers without requiring them to make a huge upfront investment, PR Ecoenergy offered a service under which customers would pay only for the end product (high pressure steam) generated by its biomass. The company supplies the briquettes and operates the boilers. Under this model, PR Ecoenergy can transfer the operations responsibility back to a customer’s control after it is satisfied that the boilers work reliably.

To make this model work, PR Ecoenergy applies multiple quality checks on both the input (waste raw material) and the output (briquettes). The tests are to make sure that the calorific value is high enough (so that the briquettes burn intensely), the ash content and the moisture content is low (so that the whole of the briquette is used to generate heat).

The company also has developed a large network of briquette manufacturers to ensure no shortage of supplies even during monsoon months. It introduced this model to its first customer in 2013 and was able to successfully transfer the boiler back to the customer after four years of operation. Since then, PR Ecoenergy has acquired other customers with the same offering.

The prevailing wisdom is that innovation is key to develop cleantech. Competitions are organized to support the latest ideas and provide startups with advice and small amounts of money. International development financial institutions provide millions of euros and dollars to banks in emerging countries to scale up “promising” new technologies.

If these organizations shifted their attention from innovation to quality, they probably would behave differently. They would appreciate that quality issues dominate the minds of customers and prevent clean technologies, many of which make eminent economic sense, from growing rapidly at the expense of quality.

Instead of providing small grants to startups, they could support projects jointly developed by large organizations and startups to test products and technologies. It is only by close collaboration between suppliers and buyers that quality is attained.

International development financial institutions would support industry organizations to set up a system to ensure quality. That is what the World Bank did in Bangladesh for its solar home system program. The quality infrastructure prioritized the following: certification of vendors and components, laboratory testing facilities, field verification and technical audits.

In Bangladesh, Rezwan Khan and his team prioritized quality by bringing back sample systems every few years and taking them apart to check whether they were working as expected. Today, the internet of things allows real-time testing of thousands of devices.

Subir Chowdhury, the international quality guru, never tires of saying everybody needs to make a commitment to a “quality mindset.” Transitioning to a clean future likewise requires a commitment to quality by innovators, corporations and customers.