The appropriateness of distributed renewable energy: a development economic perspective

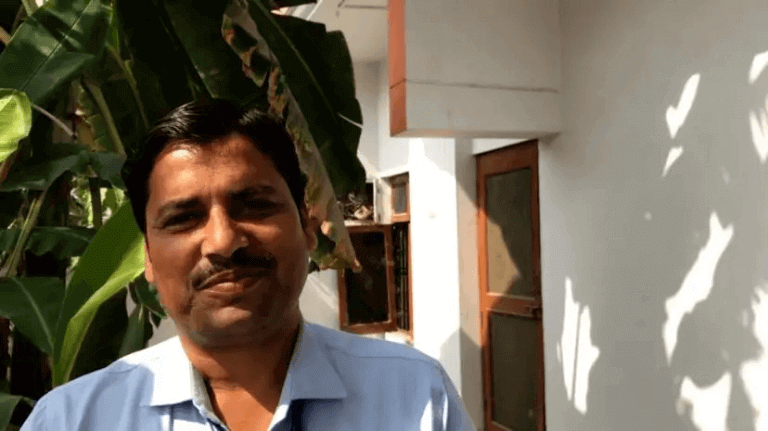

“There are no companies here and no question of getting any formal jobs,” says Sanjay Kumar Awasthi, a 45-year-old resident of the Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh. It is a common problem in the rural areas of India, which is why most young men migrate to India’s growing urban hubs. Mr Awasthi, however, has had a different career path. He joined Mera Gao Power, a startup in rural Uttar Pradesh that sets up micro-grids. Each of these micro-grids lights up 32 houses. The electricity provided is enough for a few low watt LED (light emitting device) lights and a mobile charger. For many customers of Mera Gao Power that is all they need. The children can do homework. The women can charge their phones and talk to their husbands who are often working away from home.

Many economists think that this basic lighting does not lead to economic growth. They miss the point about jobs and the multiplier effect of spending on “wage goods” in a local economy. Mera Gao Power has provided 140 permanent local jobs. These employees man the 1074 micro-grids across six districts of eastern Uttar Pradesh. Almost all its employees come from the local rural community. Since he joined, Mr Awasthi’s career has progressed well. He joined as a Collection officer at a salary of Rs. 2000 (USD 40) per month. After two promotions, he is now responsible for business development. He earns enough to put his two children through college. Like company employees in India’s urban sector, he expects his career to move quickly. In the next five years, he hopes that his job responsibility and salary will increase “in the same way as they have grown in the last 5 years”.

Other rural lighting start-ups provide more than basic lighting and mobile charging. Mlinda set up larger mini-grids that provide 3 phase alternating current. They can power homes as well as agricultural machinery. Mlinda operates in the Gumla district of Jharkhand. The agricultural machinery that can be used include pumps, rice hullers, oil expellers and small cold storages. People can use these systems to increase their agricultural income. Ms Ghasni Devi manages a women’s Self-Help Group in the Pasanga village of Gumla district that runs a rice hulling enterprise. The de-husked rice is sold to organic food stores in India’s urban centers. They “get work every day of the week”. The rice hulling machine can work with the reliable electricity provided by the mini-grid. The women workers working in the rice hulling Self-Help Group did not have any reliable regular work earlier.

The Gumla district is typical of rural India. The economy is dependent entirely on agriculture. But productivity is low so most the produce is used for their household consumption. There is little surplus that is sold to generate income. Two things could change that: provision of reliable electricity and organization of producers. Sambodhi, an impact evaluation consultancy, conducted a study of seven villages served by Mlinda. It observed that average income rose by about 20% and migration reduced by 15%.

These examples would have made Ernst Friedrich Schumacher, a German-born British economist, happy. He was also involved with the Indian Planning Commission. He published Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered in 1973. In the book, Schumacher advocated the adoption of “appropriate technology” for India and other emerging economies. Appropriate Technology tacked the problem of underemployed or unemployed. The work opportunities of the poor are so restricted that they cannot work their way out of misery. “Rural unemployment produces mass migration into cities leading to a rate of urban growth which would tax the resources of even the richest societies.” In his view, the important part of the development effort should be concerned with the creation of an agro-industrial structure in the rural and small-town areas. The workplaces must be created where people are staying now. Workspaces must be cheap enough so that they can be created in large numbers without calling for an unattainable level of capital formation and imports. They should be maintained by the local skills available. The primary need is “millions of workplaces”.

Distributed renewable energy technology is an appropriate technology for rural areas. Costs of setting one up range from INR 65,000 (USD 1000) for a basic lighting micro-grid to INR 65,00,000 (USD 100,000) for a mini-grid powering agricultural load. The installation and operations is done by local people. Complex problems can be solved remotely using Internet-of-Things (IoT) technology. The complement of technology to set up Schumacher’s agro-industrial structure in the rural and small-town areas include solar rooftops for lighting schools and health centers, solar pumps for irrigation, solar drinking water systems, solar-light equipped handloom weaving machines, renewable energy based refrigeration systems.

What would have made Schumacher far happier is the profile of people who are bringing these technologies to rural India. Col Vijay Bhaskar who runs Mlinda is from the Indian Army. He along with the founders of Argo Solar, which sets up solar panels for schools and colleges are graduates of one of the top business schools of the world: the Indian School of Business. The founders of Ecozen which provides solar cold storages are from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. The founders of Inficold, which provides milk chilling systems, are from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. The founder of New Leaf Dynamics, which provides biomass-based refrigeration systems is from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. The founder of E-Hands which sets up solar systems in remote areas is a post-graduate from the Indian Statistical Institute. Several of them forsake careers in the developed world. Ajaita Shah, the founder of Frontier Markets, studied at Tufts University. Dr Ashok Das who has developed remote monitoring of distributed energy assets used to work in Applied Materials. Mateen Abdul, the founder of Grassroots, which provides biogas engines, studied at Babson College. Piyush Jaju, the founder of ONergy used to work in Hong Kong’s financial world. The founder of Cygni which sells highly efficient solar systems and appliances holds a masters degree from Stanford. The founders of Freyr Energy which has developed a software app that helps quickly size solar systems are from Purdue and Yale. In Schumacher’s ringing words: “Unless virtually all educated people see themselves as servants of the country and that means the servants of the common people there cannot possibly be enough leadership and enough communication of know how to solve this problem of unemployment or unproductive unemployment in the villages of India”.

What would be have advised to these inspiring innovators? This is what he said in his book: “What then is missing? It is simply that the brave and able practitioners of intermediate technology do not know one another, do not support one another and cannot be of assistance to those who want to follow a similar road but do not know how to get started. They exist as it were outside the mainstream of official and popular interest.” He would have advised them to come together and collaborate. In Schumacher’s view, there was no appropriate “all-India” strategy. He would have advised them to develop what he called a “regional approach”: focusing on a few districts at a time. By pooling meagre resources and focusing combined energy in a small geographical area they would be able to create real impact and attract attention.

This blog is written as the concluding piece of the USAID supported Energy Access India Investment Readiness Program executed by New Ventures Asia and the Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship at the Santa Clara University. We were able to facilitate USD 39 million in the portfolio of companies we worked with. I thank — on behalf of my colleagues — everybody who has worked on the program. Our supporters from USAID, the mentors, the investors and most importantly the entrepreneurs and their employees. For an understanding of the lessons from the project please read the whitepaper Closing the Circuit, written by the Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship and the William Davidson Insitute at the University of Michigan. For more details on the project please visit the project website.